Why Remember Stonewall?

Almost sixty years later, we still don’t know who threw the first brick. Does it matter?

This June, I’m teaching a course called “Intro to Trans Politics” at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research. Our first session was last week, and I decided to launch our discussion of the Stonewall riots of 1969 with screenshots from the National Park Service website. The screenshots, taken from the Wayback Machine, track recent changes to the Stonewall National Monument webpage as directed by the Trump Administration, which mandated the erasure of the words “transgender” and “queer” from government websites soon after Trump was inaugurated.

As you can see below, the Stonewall page has changed considerably since January:

Comparing these snapshots, we see the opening sentence of the article change from “living openly as a gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ) person was a violation of law” to “living openly as a lesbian, gay, bisexual (LGB) person” to “living openly as a member of the Stonewall community.” In the final version of the history, not even “bisexual” makes the cut; it’s replaced in the second paragraph with “gay and lesbian civil rights.”

To be honest, my students and I shared a good laugh when we read the phrase “member of the Stonewall community.” The writer(s) might as well have written “friends of Dorothy”—one of those old euphemisms that wreaks of the proverbial closet.

When viewed as a sinister way of avoiding specificity and erasing queer identities, this revision is an absurdist misfire. But the longer I sat with that phrase, the more I wondered: is the thrice revised version of this opening sentence the most ridiculous version, or is it actually… the most historically accurate of the three? Is the phrase “the Stonewall community” a fascist workaround, or is it… a powerful, if unintentional, murmur of resistance to the fascist cooptation of identity politics?

Maybe this seems like I’m splitting hairs. My point is not actually to figure out the intentions of the person who revised the Stonewall history page or whether they are secretly resisting fascist coercion. The reason why I’m interested in this odd turn of phrase—“the Stonewall community”—is because I think it’s a useful (if ironic) corrective to the compulsive acronymization of contemporary queer politics: the way in which queer identities have been split apart and pitted against each other in service of neoliberal individualism. What if there was another way? What if there still is?

In terms of historical accuracy, nearly everyone, queer radicals included, gets Stonewall wrong. How many times have I heard someone say that Marsha P. Johnson threw the first brick at Stonewall? Or that Sylvia Rivera threw the first molotov cocktail? Or that so-and-so “started” the riots? Or that Stonewall was the “first Pride”?

It’s unclear when Marsha P. (“Pay it no mind”) Johnson actually arrived at the Stonewall Inn that evening, but it seems probable based on existing evidence that by the time she got to Christopher Street, the uprising had already started. In her own words: “I was uptown and I didn’t get downtown until about two o’clock [in the morning], because when I got downtown the place was already on fire.”

There goes the first brick theory.

As for Sylvia Rivera, she liked to be coy about her involvement. Her stories of that night differed over the years. In one interview, she said: “I remember someone throwing a molotov cocktail. I don’t know who the person was, but I mean I saw that and I just said to myself in Spanish, I said. oh my God, the revolution is finally here!”1

In another interview, she joked about throwing the “second” molotov cocktail that night: “I have been given the credit for throwing the first Molotov cocktail by many historians but I always like to correct it; I threw the second one, I did not throw the first one! And I didn’t even know what a Molotov cocktail was; I’m holding this thing that’s lit and I’m like ‘What the hell am I supposed to do with this?’ ‘Throw it before it blows!’ ‘OK!’”2

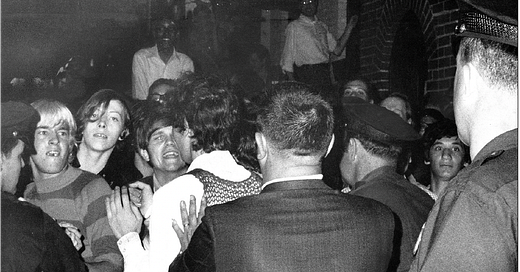

The question of who “started” the uprising is another thorny question that no ones seems to agree on. If we’re going off the testimony of Sylvia Rivera, the uprising started when she and her fellow patrons of the Stonewall Inn were led out of the bar by police officers and “cattled” up against the police vans, a common occurrence in those days:

“The cops pushed us up against the grates and fences. People started throwing pennies, nickels, and quarters at the cops. And then the bottles started. And then we finally had the morals squad barricaded in the Stonewall building, because they were actually afraid of us at that time. They didn’t know we were going to react that way. We were not taking any more of this shit. We had done so much for other movements. It was time. It was street gay people from the Village out front: homeless people who lived in the park in Sheridan Square outside the bar-and then drag queens behind them and everybody behind us.”3

In one archival “dialogue” between “Sylvia Rivera and Some Pigs,” one of the cops who was there that night recalls that after the patrons of Stonewall had been forced into the street, “One drag queen, as we put her in the car, opened the door on the other side and jumped out. At which time we had to chase that person and he was caught, put back into the car, he made another attempt to get out the same door, the other door, and at that point we had other handcuff the person. From this point on, things really began to get crazy.”4

Reading these testimonies, especially testimonies written by the rebels who participated directly in the uprising, we can begin to understand that “the Stonewall community” is actually an apt descriptor of the diverse coalition of people who took to the streets that night. There were straight homeless people who joined in from Sheridan Square. There were poor people of color from the Village who, whether queer or not, were well-versed in fighting police brutality. There were butch dykes who fought alongside drag queens even though lesbians were an underserved minority at the bar. There were poor white gay “street kids” who participated in the revolt, even though white gender-normative people were the least at-risk patrons during bar raids.

As Marc Stein explains in his book The Stonewall Riots: A Documentary History:

“Many accounts suggest that the patrons [of Stonewall] were diverse in terms of class and race. Most were probably white; a significant number were African American and Puerto Rican. Most were probably middle or working class; some were poor and/ or homeless. The large majority identified as men, a small number as women. Many likely saw themselves as gay, bisexual, or homosexual; a small minority probably viewed themselves as lesbian; others may have enjoyed same- sex sex without claiming a distinct sexual identity; some probably identified as straight or heterosexual. There was a significant and visible presence of gender- queer people, some of whom identified as butches, drags, queens, transsexuals, or transvestites. Some were hustlers or prostitutes. Most patrons were in their teens, twenties, or thirties.”5

For so many reasons, it is reductive to refer to the ad hoc community that gathered at the Stonewall Inn simply as “lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people.” In doing so, we risk overvaluing specific (and often anachronistic) categories of gender and sexual orientation to the detriment of class, race, and other intersecting identities that informed the perspectives, politics, and lived experiences of the people who patronized Stonewall that June and joined forces to defy state violence.

Jessie Gan, in an influential article about Sylvia Rivera’s legacy, describes the dangers of “strategic essentialism” when it comes to telling the story of Stonewall:

“…just as ‘gay’ had excluded ‘transgender’ in the Stonewall imaginary, the claim that “transgender people were at Stonewall too” enacted its own omissions of difference and hierarchy within the term ‘transgender.’ Rivera was poor and Latina, while some transgender activists making political claims on the basis of her history were white and middle-class. She was being praised for becoming visible as transgender while her racial and class visibility were being simultaneously concealed. Juana María Rodríguez has pointed out that making oneself politically legible in the face of hegemonic culture will necessarily gloss over complexity and difference. ‘It is the experience of having to define one’s sense of self in opposition to dominant culture that forces the creation of an ethnic/national identity that is then readable by the larger society,’ she wrote. ‘The imposed necessity for ‘strategic essentialism,’ reducing identity categories to the most readily decipherable marker around which to mobilize, serves as a double-edged sword, cutting at hegemonic culture as it reinscribes nation/gender/race myths.’ The myth that all gay people were equally oppressed and equally resistant at Stonewall was replaced by a new myth after Rivera’s historical ‘coming out,’ that all transgender people were most oppressed and most resistant at Stonewall (and still are today). This myth could be circulated and consumed when, in the service of a liberal multicultural logic of recognition, Rivera’s complexly situated subjectivity as a working-class Puerto Rican/Venezuelan drag queen became reduced to that of ‘transgender Stonewall combatant.’”

Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson were only two of the approximately two thousand people who gathered to resist police violence in the early morning hours of June 28th, 1969. The nuances of their life stories, their identities, and their politics are a reminder that nothing about the uprising at the Stonewall Inn was simple or straightforward. The event occurred at the intersection of multiple overlapping historical conditions: increased urban surveillance as a result of the ongoing war in Vietnam; gentrification and urban renewal that displaced working-class, Black, and brown communities; corruption at the city and state level, including cops who took payouts from the mafia to keep gay bars running; the rise of radical liberation groups like the Black Panthers.6

The enduring power of the Stonewall myth is not derived from the “facts” of what “happened” that night: indeed, the facts have always been contested. Nor is it derived from the uniqueness of the uprising or its watershed influence on social conditions for queer people.

The Stonewall riots were not unique: they followed as string of sit-ins, pickets, uprisings, and revolts by sexual and gender minorities throughout the 1960s. They happened at Cooper’s Donuts (1959, Los Angeles), Dewey’s Cafeteria (1969, Philadelphia), the Drag Masquerade Fundraiser for the Council on Religion and the Homosexual (1965, San Francisco), Compton’s Cafeteria (1966, San Francisco), and The Black Cat (1967, Los Angeles), to name a few. And the Stonewall riots were not particularly successful either: a small fraction of Americans knew about the uprising at Stonewall in its direct aftermath, and it took concerted organizing on the part of activists to begin moving the needle on social acceptance and political belonging for queer people in the ensuing years, and then usually only for white gay and lesbian people.

It wasn’t until the first annual Christopher Street Liberation March in June of 1970 that the Stonewall riots started being touted as a watershed historical event and a turning point for gay liberation. Almost as soon as commemorations began, the memory of the event was contested, and internal rifts among gay, lesbian, bisexual, and trans activists deepened.

Rather than marking the beginning of gay rights, we might view Stonewall as marking the end of something else: the coalitional and intersectional movements that sustained sexual and gender minorities throughout the 1960s across oppressed identities. This is not to romanticize the social movements of the 1960s, which certainly had their fair share of internal rifts and internecine conflict. Rather, this retelling of Stonewall offers us the chance to lament the radical possibilities that are foreclosed when social movements put identity policing above collective power, a problem we continue to face today.

As we come up on the 56th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising later this month, we find ourselves in a political moment where government officials are trying to legislate trans people out of existence; where Black and brown immigrants are being deported in troves in increasingly violent, illegal, and inhumane purges; where child-bearing people are being treated as breeding machines and forced to carry fetuses to term; and where anti-trans, anti-abortion maniacs are assassinating elected officials. In other words, we are living in a political moment where single-issue politics are not only myopic, but actively harmful. People can no longer pretend “trans rights” are separate from “gay rights” are separate from “choice” are separate from “racial equality,” if they ever did in the first place.

In this context, we would do well to consider what we, as the queer community, are actually commemorating when we commemorate Stonewall.

I, for one, am drawn to the idea of commemorating the Stonewall community this June. Without this community, there would have been no uprising. After all, only a fraction of the patrons of Stonewall were directly targeted by the police that night—the Black and brown ones, the butch ones, the transfeminine ones. Others were released and could have gone home. Ultimately, it was the tentative, ever-shifting, uncomfortable, and difference-ridden community of variously marginalized people at the Stonewall Inn that mustered the courage to resist the violent status quo, not a single “hero” or a homogenous group of “gay” people “coming out of the closet.”

Some people did decide to go home that night. Some people, especially the most privileged people, did stick to the fringes of the uprising. But there were others who decided to remain, who decided that none of them were free unless all of them were free. The people who were not handcuffed fought to free the ones who were. The people who were not dragged to the paddy wagons did what they could to liberate the ones who were, to keep the cops’ batons from beating their friends even if it meant that they themselves might be beaten. They did this knowing that resisting the police would put them all at risk of arrest, physical violence, and even rape, because they had seen these punishments meted out over years of similar raids at gay bars like Stonewall.

They did this not because it was the first uprising of its kind, but because it was one in a series of uprisings by queer people, Black people, draft resistors, women, poor people, Native American people, and other disenfranchised Americans who came together to build collective power in defiance of the oppressive, privileged few who called the shots for everyone else.

Instead of looking for one perfect uprising, one ideal moment of resistance to the Trump administration, we should be looking to the cumulative power of constant resistance, of persistent organizing and cross-pollination across social movements.7 We should be building and engaging in resilient communities that not only respect but require difference in order to function. Communities that encourage people to think in terms of collective safety rather than individual liberty. Communities like the one that fought back on June 28, 1969.

Happy Pride everyone.

Quoted in Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries: Survival, Revolt, and Queer Antagonist Struggle. Untorelli Press, 2013. http://archive.org/details/untorelli_2013_transvestite, 17.

Ibid., 33.

Ibid., 12.

Ibid., 16. The cop who is quoted was named Seymour Pine and he was the Deputy Inspector in charge of public morals in the first division in the police department.

Stein, Marc. The Stonewall Riots: A Documentary History. New York: New York University Press, 2019, 3.

Stryker, Susan, Transgender History, Seal Press, 2009.

See Cohen, Cathy J. “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” In Sexual Identities, Queer Politics, edited by Mark Blasius, 200–228. Princeton University Press, 2001. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv19fvxz3.12.

Well done!

Hey this was really brilliant and well said!!!