Last Friday I spent the evening at a bar full of lesbians wearing flannel. I mean this literally—the dress code for the gathering was flannel. I wore one of my wife’s vintage green and black plaid shirts, a hand-me-down from her mother who wore it in the 70s. By the end of the evening us flanneled queer ladies had taken over this otherwise straight-presenting bar with our seltzers and our polycules. There were only a couple of straight dudes left in the place at 10pm. We joked about them, wondering what they thought the gathering was for. A networking event? A group of gals being pals?

I didn’t know how much I needed this kind of gathering until I was a part of it. Queer spaces are the only ones where I feel like I can relax these days, where everyone else is feeling some version of what I’m feeling, so I don’t have to explain myself or fill them in on the bad news. We can talk to each other knowing that the jokes we make and the stupid stories we share are not stemming from blissful ignorance of the state of the world, but from our collective need to protect our joy in a time of crisis.

As I chatted with some fellow queers at the gathering last Friday, we got on the topic of digital preservation. What if they start deleting things? Someone asked. We all knew what she meant. “They” being the government and the CEOs of tech companies (is there really a difference anymore?). “Things” being the traces of queer lives, queer stories, queer history, and queer culture so recently made available to us by the internet, now so easily taken away from us by the same. (It was only in 2003 that the Supreme Court decided, in Lawrence v. Texas, that U.S. state laws criminalizing sodomy were unconstitutional. The next year, Facebook was created.)

Make copies of things, I said, keep physical records. Books, documents, vinyl records, photographs.

As we kept talking about the importance of preserving material traces of queer history, the conversation naturally shifted to archives. I happened to be wearing a Lesbian Herstory Archives t-shirt that evening, a vintage shirt I had picked up at the LHA merch sale they held in December of last year.

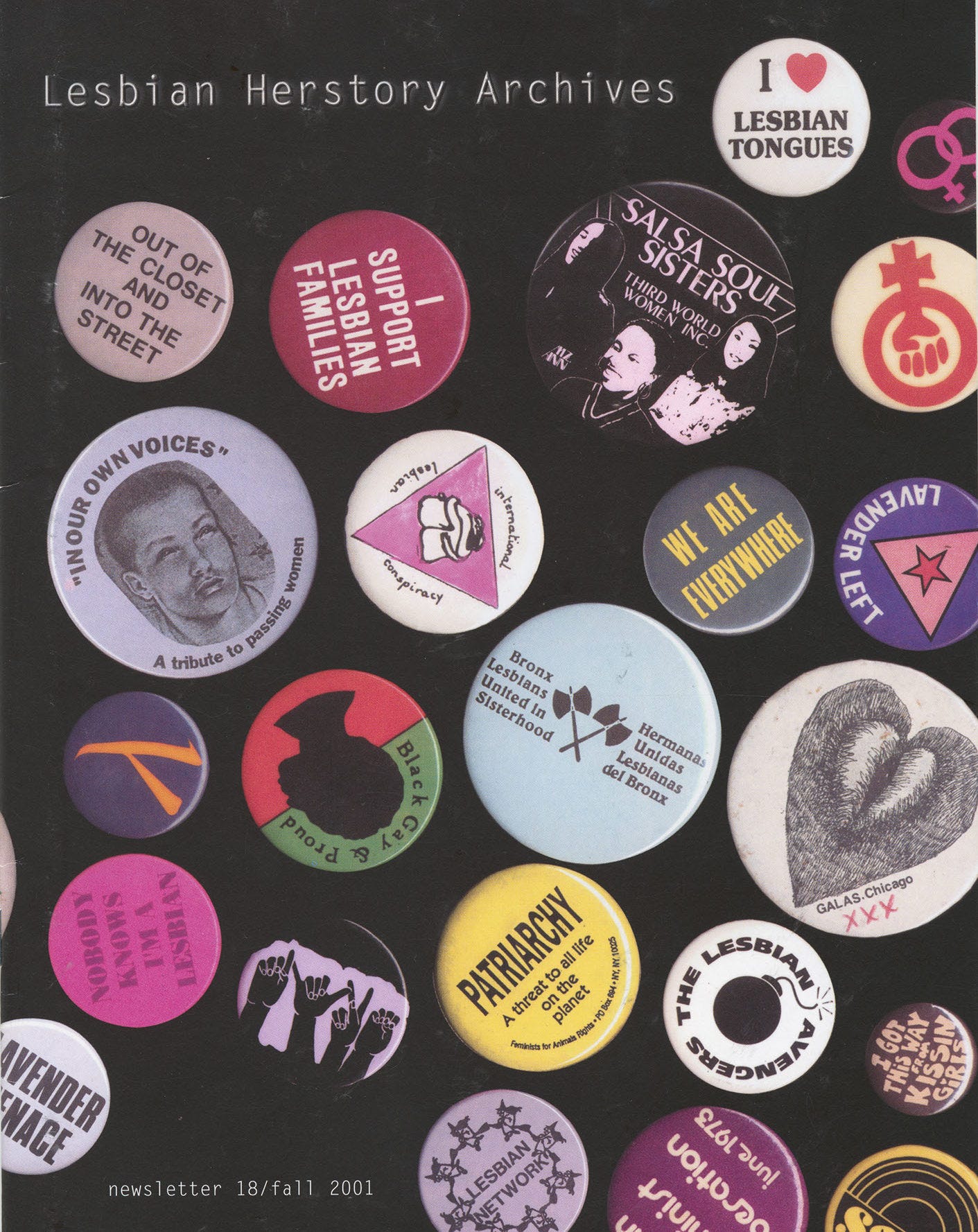

I remember that day vividly because there was a line of queers snaking down and around the block. It was a freezing cold Saturday morning on a sleepy side street in Park Slope, and passerby were staring at us as they drove by in their cars. Who were all these women and trans people and nonbinary folks standing around shivering outside a nondescript brownstone? It must have been an odd sight to those not in the know. But here we were, eager to have our own little piece of this shared herstory, rifling through sweatshirts with handprinted cats and carabiners and lipsticked lips on them, searching for vintage buttons that said “Archivists Make It Last Longer.”

For those unfamiliar with archives, they are institutions that preserve primary sources in their original form for researchers (and sometimes the general public) to consult on-site. So, for example, if you were to go into a public library, you would find books and DVDs and CDs that you can check out. These are copies of items that are available in other places. If you go into an archive, however, you might see a handwritten letter that has no duplicate anywhere in the world. You might see a rare book, like Eve Adam’s Lesbian Love from 1925, the only extant copy of which once belonged to Yale’s Sterling Library, from which it eventually disappeared. (Later, historian Jonathan Ned Katz found a copy through a woman named Nina Alvarez, who discovered the book in the lobby of her apartment building in 1998. But that’s another story…)

Archives have a long, tortured history. For centuries, religious institutions like the Catholic Church were some of the only places where archival documents were preserved. Ancient documents were often destroyed by fire, war, natural decay, or changes in government. For the past several hundred years, university libraries have been key repositories of archival material, as have museums and, since roughly the French Revolution, state archives.

Archives are selective in what they chose to store. These materials take up a lot of room. They are heavy and sometimes fragile and often require special conditions to prevent deterioration, like temperature, light, and moisture control, not to mention security. There is one literary archive in France, IMEC, that makes you weigh the documents before and after you look at them to guard against theft. These is just one example of the kind of measures that are usually taken to protect archival collections.

Institutions like universities, national archives, and museums have specific criteria for what they are willing to accept as donations. Sometimes these criteria are thematic or geographical or chronological in nature. Because of these criteria, artifacts of queer and trans lives have rarely been preserved as such in official archives. In countries like the US where sodomy, cross-dressing, and gender deviance were criminalized until quite recently (and are being criminalized again), material traces of queer people’s lives were highly sensitive and hard to come by for much of the twentieth century. Archivists, for the most part, didn’t want them. If they did, it was often in the form of police records or medical files, both of which contributed to the image of queer people as criminals and mentally ill outsiders. Queer people, for their part, either destroyed documents from their lives out of concern for their safety, wrote them in code, signed them by different names, or kept them hidden in their own homes.

Joan Nestle, one of the co-founders of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, has written at length about this particular aspect of queer history: “[…] families burned letters and diaries,” she writes. “…our cultural artifacts were often found in piles of garbage or on bargain tables. When we first started the archives, these were new ideas but now with the international lesbian and gay archives movement, with the flourishing of a lesbian and gay social history movement and with a raised consciousness about the importance of sexual choices in biographical studies, we hope the message has been given — no more pyres of same-sex love letters.”

No more pyres of same-sex love letters.

As I discussed the history of queer archives with the lesbians gathered at the bar last Friday, I found myself tearing up (as I always do) while explaining the plans that LHA volunteers have in place should a fire or other disaster threaten the collection. Maxine Wolf, one of the archivettes who has helped sustain the LHA collection over the years, points to this kind of commitment as a major difference between community-run queer archives like LHA and state or university archives. Should a fire break out in a state archives, what would they be most likely to save: lesbian love letters, or “important” government documents? At LHA, the answer is clear.

Lesbian archives (like other community archives built by marginalized communities in the 1960s and 1970s) were committed to shifting the emphasis of archival practice away from “historical importance” as defined by mainstream culture and toward collective memory and cultural preservation, as defined by those who donated to, volunteered for, visited, and maintained the archives. As Ann Cvetkovich argues in her book An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures, “Queer archives are composed of material practices that challenge traditional conceptions of history and understand the quest for history as a psychic need rather than a science.”

The Lesbian Herstory Archives started out as a small collection of books and documents stored in an extra room in Joan Nestle and Deb Edel’s apartment on the Upper West Side in 1974. The bookshelves were held up by empty coffee cans, and there was no catalog or formal process for viewing materials. At one point, two of LHA’s founders took the entire collection—ten milk crates worth of materials—with them to a rural lesbian commune in Tennessee. After the couple broke up and left Tennessee, Deb Edel came to drive the collection back to New York City, where it stayed until LHA purchased the Park Slope brownstone in 1992.

Like many of the queer archives that were founded in the 1970s, LHA was committed to the safety and sustainability of its collection above all else. Keeping their collection in someone’s home meant that they did not have to worry about being kicked off of a commercial lease or vandalized by passersby on the street. They didn’t publish the address of the archives in those early years, only the phone number. People had to call to be given the address.

“Deb and Joan agreed that the first ten years of the Archives would be to build the trust of the communities it was serving. They were determined to keep all the services of the Archives free, to not seek government funding, and to build grassroots support for the project. To accomplish this, Deb and Joan had carried around early journal issues, photographs, letters, and so on, in shopping bags, speaking to whoever invited them. The venues ranged from living rooms where all present were sworn to secrecy, to women’s festivals, gay church and synagogue gatherings, classrooms and bars.” — “Our Herstory,” Lesbian Herstory Archives webpage

The mission of the Lesbian Herstory Archives feels as relevant now as it did fifty years ago. Part of the reason why LHA and grassroots institutions like it are relatively well-situated to survive the austerity and censorship of the Trump administration is because they have retained their autonomy. By-and-large, they are not beholden to federal grant money or directives from the Department of Education. They run on volunteer hours and donations from the community. And most importantly, they are community spaces that are committed to providing access to queer history and culture for those who have traditionally been denied it.

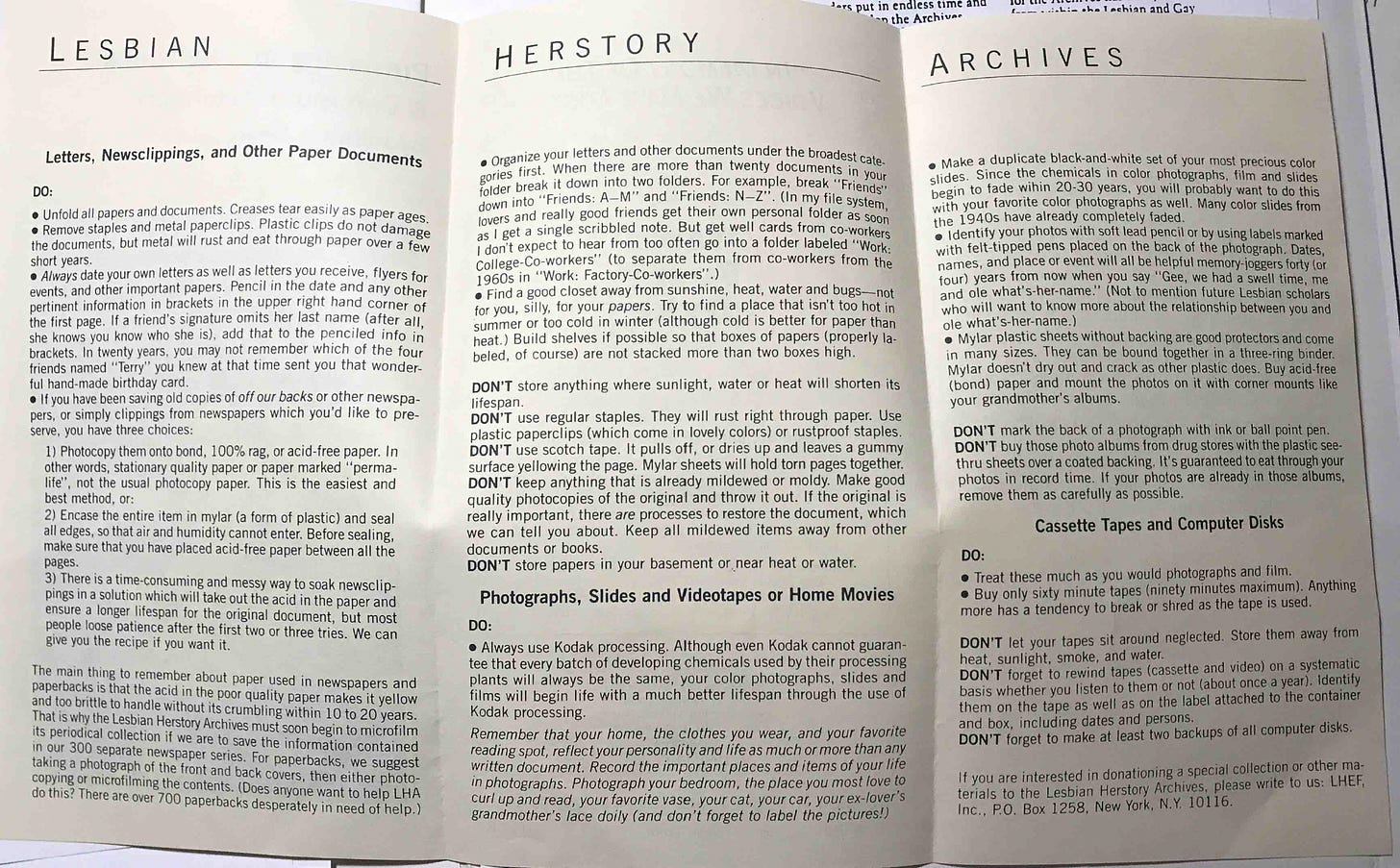

These archives exist, and continue to thrive, because people contribute to them. They contribute their personal papers, photographs, letters, t-shirts, books, and buttons. They contribute their money. They contribute their computer skills or their library sciences training or their knowledge of graphic design. They contribute their time as volunteers to keep the space open to the public. They plan visits to the archives with their friends and lovers and spread awareness of its work.

Queer history is only as safe as the people who make it and protect it, and every one of us is capable of contributing to that legacy. In fact, it is imperative that we do.

As we head into the third week of this hellish administration, I encourage you to find ways to share and preserve queer history in your communities and with your people. Host book swap parties. Build little free libraries in your neighborhood and fill them with queer books. Sit down with your partner(s) and start organizing your files (or printing out digital files) by year and theme. Print out pictures of you and your friends at Riis Beach or dressed up for a Chappell Roan concert. Make scrapbooks with your chosen family and write down some of your favorite memories. Find queer elders to befriend and ask them if they will sit down for an oral history interview. Record the interview and donate it to your local queer or lesbian archive.

We have always existed, and we always will.

To live without history is to live like an infant, constantly amazed and challenged by a strange and unnamed world. There is deep wonder in this kind of existence, a vitality of curiosity and a sense of adventure that we do well to keep alive all of our lives. But a people who are struggling against a world that has decreed them obscene need a stronger bedrock beneath their feet. We need to know that we are not accidental, that our culture has grown and changed with the currents of time, that we, like others, have a social history composed of individual lives, community struggles, and customs of language, dress, and behavior—in short, that we have the story of a people to tell. To live with history is to have a memory not just of our own lives but of the lives of others, people we have never met but whose voices and actions connect us to our collective selves.” (Joan Nestle, from A Restricted Country 1987)

Check out these resources and donate to the work of LGBTQ+ archives:

June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives

Black Lesbian Archives Substack

Love this! Thank you for writing so beautifully about queer archives and the Lesbian Herstory Project!

I loved this piece so much! And I felt so seen because I also always tear up when I talk about queer archival history 🥲